Every year, the Mycological Society of America gathers for an annual conference where mycologists present their research. The Hibbett Lab is attending this year’s conference in Flagstaff, AZ, and presenting our progress with the Lentinus project.

On this page, you can view our poster, supporters, some supplementary data, and links to pages describing our project further. Poster presenters: Thomas Roehl, Sofie Irons, Devon Rose Leaver.

Research Supporters

We thank the Massachusetts Audubon Society Ipswich River Wildlife Sanctuary, Illinois Mycological Association, and North American Mycological Society for their support, as well as colleagues and community mycologists who have donated specimens (Manfred Binder, Laszlo Nagy, Brian Looney, Larry Millman, Theresa Park, Dave Layton, Annie Weisman, Garrett Taylor, Alisha Millican, Sylvia Holser, Django Grootmyers, Daniel Molter, Rohr, A. Sandor, Rytas Vilgalys, the Boston Mycology Club, and the Alabama Mycological Society). We also thank our lab members who have contributed to this project over the years (Alicia Knudson, Zhangyi Xu, Thea Henry, Iris Knowles, Christina Martin, Prasanth Prakash Prabhu, and Isaac Perkis). This research was supported by a Clark University Faculty Development Award and Klein Endowed Professorship (to David Hibbett) and a LEEP undergraduate research award (to Devon Rose Leaver).

Supplementary Data

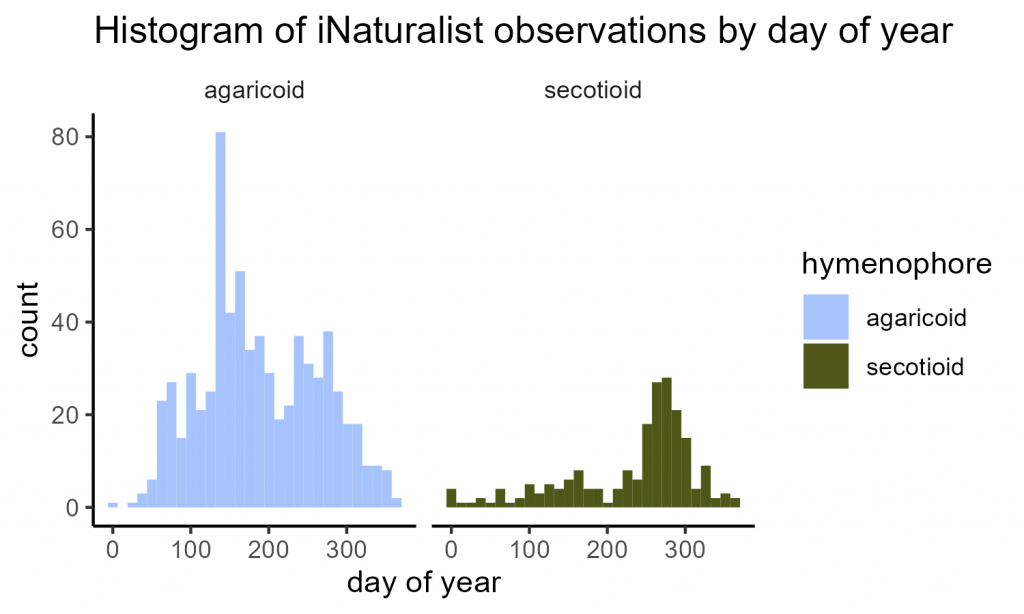

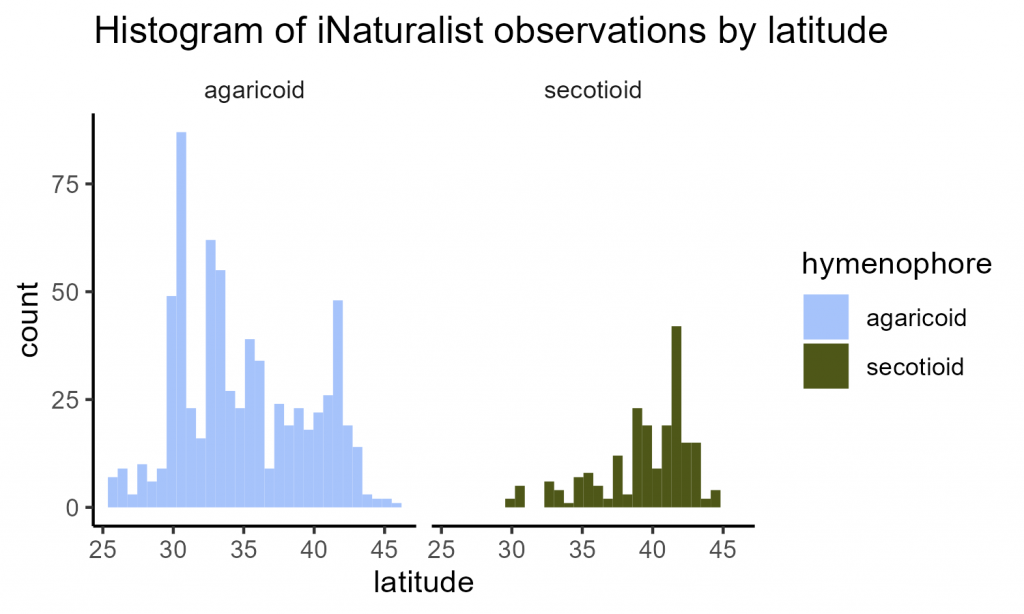

We recently finished our assessment of the US iNaturalist observations of L. tigrinus and some analyses were not completed in time to be included on the poster. But, we’re very excited about the results so they are included below. Using the online data, we checked that each record was properly identified and assessed its morphology – only records that could be identified as agaricoid or secotioid were used in this analysis, giving us a total of 892 records.

Seasonality

One question we had from fieldwork was whether the agaricoid and secotioid forms appeared preferentially in different seasons. While collecting in August last year, the majority of specimens we collected were secotioid. This year, however, while collecting from the same site in June, the majority of specimens we collected were agaricoid.

Is this a pattern, or just random chance? To check, you’d want a large dataset from across the mushroom’s range – which we now have from the iNaturalist data.

The national data follows our local observations surprisingly well: the agaricoid form tends to fruit earlier in the year, while the secotioid form tends to fruit later. It appears that the agaricoid form has two peaks: one around May and one around October. The secotioid form also has two peaks around the same times, but the fall peak is much higher than the spring peak – 60% of secotioid observations fall between September 1 and November 30. Statistically, this difference in seasonality between the two morphologies is significant (Wilcoxon rank sum test, W = 45583.5, p = 4.36e-14).

Why is this important? One thing we’re investigating is whether there is population structure based on morphology. We now have two processes that could result in population structure: the morphology itself (spores from agaricoid and secotioid mushrooms are likely dispersed by different mechanisms) and time of spore dispersal.

Range Differences

Looking at the map and bar graph of regional frequency, it seems that the secotioid form is more common in northern states and less common in southern states. In fact, it’s unreported from Florida and anywhere west of the Great Plains.

Again, the statistics back up this observation: differences between the two forms in latitude and longitude are both significant (see table below). However, latitude seems to have a stronger impact on range, since its p-value is much lower. Because none of these variables is normally distributed, they were all analyzed using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Anything p-value less than 0.05 is considered significant.

Wilcoxon test results: significance of hymenophore’s impact on latitude, longitude, and day of year of L. tigrinus collections

| Variable | W | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| longitude | 59390.5 | 1.08 x 10-3 |

| latitude | 30819.5 | 7.91 x 10-34 |

| day of year | 45583.5 | 4.44 x 10-14 |

Why is this important? We are interested in the evolution of the secotioid form and understanding its distribution will help us understand its evolutionary history. Looking at the map, it looks like the mutation appeared around Indiana and has been spreading east and south. This would suggest a recent origin of the secotioid form – we could be watching evolution in action. On the other hand, the secotioid form could be finished spreading. This would suggest that environmental factors keeping it balanced with the agaricoid form and preventing it from spreading to the Southeast. Which is correct? We can’t tell, but we now have some idea of what to look for!