Lentinus tigrinus, commonly called the Tiger Sawgill, is an exceptional mushroom. At first glance, it appears commonplace – a drab umbrella-shaped agaric (gilled mushroom). But look further and it’s one of the most unique mushrooms in North America. Sure, it’s a gilled mushroom, but it’s actually a polypore relative. How did that happen? Oh, and about those gills… you’ll often find it with its gills sealed shut – trapping the spores inside. Wait, how does it reproduce? And I know mushrooms like to grow in wet places, but specifically growing in swamps might be taking the concept a little too far! Not only do these features make the Tiger Sawgill something mushroom nerds can fawn over at forays, but they also pose serious scientific questions: how do new mushroom shapes evolve? how can one species have two wildly different shapes in the same environment? how do genes control mushroom formation? But before we get to the science, we first must learn more about our organism.

Morphology

The Tiger Sawgill is a medium-sized mushroom with a pale grey-white pileus (cap), 1-10 cm in diameter, with dark gray-brown fibrillose scales. In some specimens the scales are dense, giving the cap a dark aspect, but in others the scales are sparse and the pileus has a smooth light colored appearance. The pileus is often umbilicate (with a depression in the center).

The surface of the stipe (the stalk holding up the pileus) looks similar to that of the pileus. It, too, is cream-colored to medium brown and covered in darker scales. European collections of L. tigrinus also have a thin ring of fibers on their stipe – the remains of a partial veil (a membrane covering the young gills). This veil is never seen in North American collections.

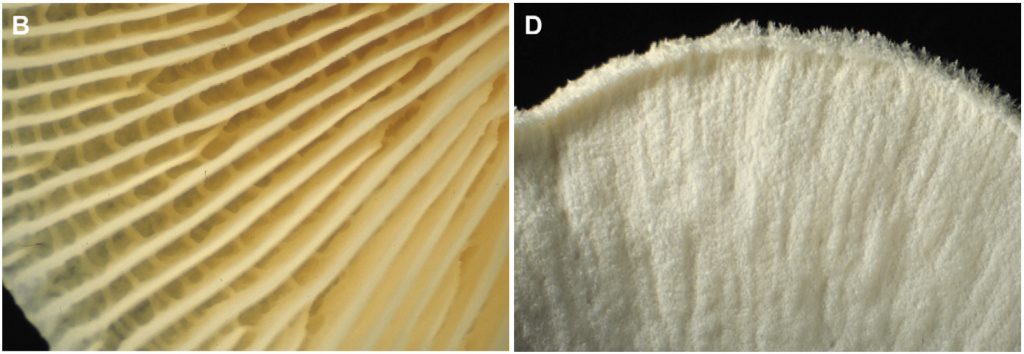

Lentinus tigrinus has two morphological forms, distinguished by the surface underneath the pileus. The standard form, found in both North America and Europe, features gills on the underside. We call this the agaricoid form. The gills are decurrent (running down the stipe) and have toothed margins (hence, “sawgill”). Like other gilled mushrooms, the gills function to produce spores and disperse them into the air. Spores are white in deposit, cylindrical, and inamyloid.

The second form, which we call secotioid, is smooth or rippled underneath; the gills have been covered by an outer layer of pale tissue to form a continuous membrane. Spores still develop on the enclosed gill tissue, but the membrane traps them inside the mushroom. The membrane often contains small gaps where it has torn or been eaten by insects. The secotioid form is found exclusively in North America.

Interestingly, both the agaricoid and secotioid forms coexist in North America. All populations we have surveyed contain both forms, usually with about equal numbers of each. Both forms can appear side by side, and we have even found the two forms sharing the same small stick!

What gene causes the secotioid form?

How is evolution acting on these mixed populations?

Are the North American and European populations separate species?

The entire fruiting body has a tough, pliant texture (lentus is Latin for “tough”), which is due to the presence of thick-walled, branched binding hyphae. The durable texture means the mushrooms will keep their shape underwater and can last through the winter if untouched by insects.

If you have a microscope, you can look for hyphal pegs on the surface of the gills. These structures, along with the cylindrical spores and binding hyphae, suggest that this gilled mushroom is actually closely related to certain centrally stipitate polypores, such as Polyporus arcularius and P. brumalis (which have in fact been transferred to Lentinus). The genus Lentinus sensu stricto is a gilled member of the order Polyporales. You are most likely to confuse this species with Lentinellus michneri (aka Lentinellus omphalodes), which is actually in a completely different order, the Russulales. That species, however, lacks scales and has much more distinct and irregular serrations on its gill margins.

How did a polypore evolve gills?

Habitat

Lentinus tigrinus, commonly called the Tiger Sawgill, is a surprisingly consistent mushroom. Mushrooms are typically known for their unpredictability, but if you’re in the right habitat during the summer you will find L. tigrinus. But despite its astounding reliability, the Tiger Sawgill rarely appears on collection tables at forays. Why? Because its preferred habitat is wood partially submerged in water – not a place you’ll find many mushroom hunters!

Although rarely collected on forays, L. tigrinus is widespread in North America, Europe, northern Africa, and the Middle East. Its North American range includes anywhere east of the Great Plains, although there are also scattered reports from the West. Mushroom Observer includes several observations from the western US, including two in Arizona and one in California. The great mycologist Harry Thiers, who wrote a classic paper on “The Secotioid Syndrome” (in which he sadly did not mention the secotioid form of L. tigrinus), collected this species in Arizona in 1970, and his material is now in the culture collection and herbarium of the USDA Center for Forest Mycology Research.

In both Europe and North America, the Tiger Sawgill grows on the wood of hardwoods – typically willow, poplar, elm, or maple – in and around waterways. Although it can be found in upland habitats, it is most often collected near water – in riparian forests subject to periodic flooding. North American populations have a particular fondness for Silver Maple (Acer saccharinum) wood and routinely appear on Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis). Its host trees are well adapted to life near the water, quickly putting up new shoots and disposing of older damaged branches. They tend to leave a lot of dead wood behind as they grow and L. tigrinus seems to monopolize this debris. The fungus is a decomposer and causes a white rot – it preferentially breaks down the brown lignin in wood to leave behind the white cellulose. Some specimens of L. tigrinus, including the Californian specimen on Mushroom Observer emerge from sandy soil on riverbanks, presumably from buried wood.

The Tiger Sawgill is remarkable for its dominance in this habitat. In our New England collecting sites, nearly every piece of wood in the river has L. tigrinus fruiting on it in the summer. Not even a “flash drought” in 2022 could stop this fungus – in a summer where the bone-dry soil meant empty baskets for even the most seasoned foragers, L. tigrinus remained bountiful. As the water level dropped, the mushrooms simply grew lower down on previously-submerged wood.

Is the secotioid form an adaptation to life in a dynamic waterside habitat?

How do these environmental conditions impact spore dispersal?

Despite the reliability, accessing locations favored by the Tiger Sawgill can be a challenge. It’s difficult to find a path through the sodden mud riddled with debris. There are mosquitos, ticks, and flies to deal with. In southern New England, the habitats favored by L. tigrinus are often choked with greenbrier and poison ivy. Hunting the Tiger Sawgill can be a painful experience. However, a pleasant and productive approach is to go mushroom hunting by canoe. Lentinus tigrinus frequently grows from logs that are emergent from water – a canoe lets you get right up to those logs without getting wet (well, depending on who’s paddling)!

Learn more about L. tigrinus on David Hibbett’s Lab site: Recognizing L. tigrinus and Where to Look.